Label in Name requires that the visble label for a control be "present" in the accessible name (AccName), which seems like a success criterion that should be easy (SC) to meet on the face of it, but I tend to have to fail sites on this SC pretty much every time I put my testing hat on. Let's look at this in detail and try to understand where developers often go wrong.

When I was a kid growing up in the UK, there was a TV game show called Catchphrase and today I have just learned that it was based on an American TV show of the same name, which is good as more folks may get my cheesy jokes and references. The original UK version was hosted by an Irish chap, a comedian named Roy Walker and the game would typically show a crudely animated image (it was the late 80s/90s) that would have an animated character Mr Chips pointing at something or otherwise acting something out to give the contestants a clue as to what the image depicted. The image would always depict a catchphrase that may be used in regular language. The reason why I am making this reference is because Roy's primary catchphrase was always "Say what you see" and I think that fits perfectly with the intent of this SC.

"For user interface components with labels that include text or images of text, the name contains the text that is presented visually."

-- WCAG

On the face of it, it really is as simple as it sounds, if we have a button which is of course a type of user interface control and that button has a label that is visible to users, then that visible name MUST be present in the AccName. On the Understanding doc it is noted that a Best Practice is to ensure the visible part of a control's AccName is front loaded, it is the beginning of the string of text that forms the overall AccName. A better Best Practice would be to ensure the visble label and the AccName are identical, although there are some situations where that may not be possible.

Just to be clear, if a control does not have any form of text label, this SC does not apply. We would of course need to ensure it had an AccName and if it did not, we would reach for 4.1.2 Name, Role, Value (A) or potentially 2.4.4 Link Purpose (In Context) if it were a link with no Accname, although either would work, here. What matters is it gets reported and fixed. As an example a magnifying glass on a Search input, a 'hamburger' icon on a menu button or social media icon links would not fail this SC, if they were icon only controls/links, as the visible label is an icon and not text or not an image of text.

The SC applies to buttons, links, inputs and any UI controls that can be operated by a user and have a text label.

2.5.3 Label in Name, Understanding Document

The intent of this SC is to make operation of sites for users of voice input software more predicatable and easier, in that when they see a control with a visible label called "Settings" they can simply say what they see and instruct their software to "Click, Settings" and as if by magic the Settings button will activate and do whatever it was supposed to do.

Labels are in fact names, but in accessibility terms, a label will typically mean a visible identifier which is positioned close to a control (for inputs, etc) or inside a control, for buttons, etc. The name of a control is what the browser computes for a control, and passes to the accessibility tree. So a label is visible and a name (AccName) is programmatic, they do not have to be different, but often are, hence why this SC exists.

The majority of users do not access the programmatic name of controls, we provide users with a user interface (UI) for operating our sites and that UI is their single source of truth. They see an input with an adjacent text label of "email", and they would understand this to be a field that they can enter their email address into. Screen reader users do access the AccName, as that is exactly what their screen reader will announce to them.

Voice input users can see the interface and read the labels, just like non-AT users do, so when they need to activate a control, the only information they have on that control is the text that is presented visually, they say what they see. Due to the way that both screen readers and voice input software work, they access the accessibility tree, which is constructed by the browser. The accessibility tree does not care what colour something is, what size it is or what the visible label is, it receives programmatic information on elements which have computed names, roles, values/states and relationships, etc. So when a control has an AccName that differs from the visible label, this is where our voice input users encounter problems. The browser isn't doing anything wrong and neither is the user, the problem was created by the developers.

Where developers go wrong

Where developers often go wrong is by giving screen reader users too much information, such as visually hidden instructions and this can and often does cause an issue for voice input users. Let's take this example code:

<nav>

<button

aria-expanded="false"

aria-controls="somePanel"

aria-label="Click this button to access the site navigation">

<i class="fa-hamburger"></i>

<span> Menu</span>

</button>

<div id="somePanel">

<!-- Stuff -->

</div>

</nav>The HTML above is the starting point for a common disclosure widget, which is a <button> inside a <nav>. We can determine that accessibility has at least been considered by somebody, as we have HTML5 elements, we have the aria-expanded state and we even have a programmatic reference with the aria-controls property with a valid IDRef. We have an icon inside the <button> and some visible text which is "Menu", so we have met the requirements for 4.1.2 Name, Role, Value and 1.3.1 Info and Relationships. Awesome that's a great start, but there is one glaring issue.

Our old friend the Accessible Name and Description Computation (algorithm) rares its head. So whilst sighted users can see that the control is visually labelled as Menu, what they see, is technically a lie. For a person that can see the control and does not use either a screen reader or voice input software, they will likely never know of the lie. They read a label and then interact with its control in their usual way, they really wholly on the UI and the accessibility tree has no effect on them.

A screen reader user that has at enough vision to make out the text and icon will get a mismatch, as what they see is not what they will hear. This is unlikely to be a showstopper (in our example), but it's still a mismatch and could cause some confusion. Unfortunately this probably wouldn't be the most inaccessible thing they encountered that day, as at least this will work, it's far from great, but it's not functionally inaccessible, assuming the AccName is completely unrelated to the control.

A blind screen reader user will not be aware of the visible text, they will hear the AccName only, again, this is not "inaccessible", to them, it still works, it still makes "enough" sense, but, I know that superfluous instrcuctions in AccNames will get really old, really quick for screen reader users and pretty much the entirety of that label is completely redundant, so let's break that down:

- "Click", Our screen reader user made it to your site, they don't really need to be informed on how to operate something as basic as a button, they did plenty of "clicking" to get to where they are

- "this button", they know it's a button, their screen reader told them that. The developer used the

<button>element, they made sure this info would be passed to the accessibility tree and I'm sure our screen reader user doesn't appreciate unnecessary repetition, repetition (sorry) - "to access the" implies that in its current 'unclicked' state, the site navigation is unavailable, the developer told them that already when they used

aria-expanded="false", so our screen reader user knows that the related panel would not be currently exposed, as the state informs them it is collapsed - Finally, we are left with "site navigation", which is technically what it is, that would be the only bit of info they would actually need. I personally use "Menu", as it's more succinct, it's universally understood and the user would know they were in a navigation landmark, because I would have my "Menu" inside a

<nav>element. But navigation would work fine, too, it is a little repetition, but not unnecessary repetition, but if using "navigation", then of course, the visible label must also match, and as "Navigation" is a much longer word than "Menu", it's more common to see "Menu" next to the icon, as space is typically at a premium on "mobile" displays, which is where this type of widget is more commonplace

So, our voice users, whether they be a fan of Catchphrase or not, will say what they see and absolutely nothing will happen because there is no control on the current page that has the AccName "Menu", and that info would not have been passed to the accessibility tree. So, in Catchphrase terms, Roy would say his other catchphrase "It's good, but it's not right" and that will be the end of that. Now, voice input software does have alternative ways to navigate sites that have poor labels, such as "show, grid", "Show labels" or "show, numbers", I'm not going to explain these, they're extra steps, extra unnecessary steps and they absolutely are not an excuse to meet the SC.

Is this just best intentions?

Honestly, I'm not the worlds's most optimistic developer/tester, but when I encounter this problem I usually put it down to best intentions and it's usually pretty evident it's one of the following:

- A developer tried to help, they tried their best, but do not fully understand the broader scope of disabilities and WCAG and erroneously assumed screen reader users need additional instructions, for basic controls

- The framework the developer used, tried to help, but did not have a full understanding, either

- The Framework had decent accessibility, but the developer changed the visible label and "forgot" to change the AccName

There are undoubtedly a couple of more, as one example, as many folk have jumped on the AI Hype Train, then there will undoubtedly be instances in the wild, where AI has spewed out some not very good HTML, because, errm AI.

So, what about Best Intentions, when a developer uses the correct pattern like in my earlier HTML example, but also, they whack an aria-labelon, for good measure? From a tester/developer perspective, I can at least understand what they were trying to achieve. In some respects, it's great that developers are "trying" to make accessible interfaces, but also, it's not great for the voice input users who are seemingly forgotten about, in that they now have a barrier that wouldn't have been present, had that dev just left ARIA in the toolbox.

ARIA is a very powerful tool, it's not like tomato sauce on our chips (fries) where we may just give our chips or fries a generous coating, perhaps thinking that the more there is, the better. The inverse is kind of true, in that the less ARIA there is, is often (not always) better, but if somebody doesn't know how to use ARIA, then, no ARIA is usually better than bad ARIA, as is often said.

So, by "trying" to help screen reader users and focusing solely on their experience by providing them with instructions in hidden text, we can actually make the experience much worse for other groups of users, especially voice input users.

A knowledge of the AccName and AccDesc algorithm is a helpful tool, it has a computed representation built into the DevTools, so developers and testers can access an element's name calculation, this is a very useful tool to me, as I can take a screenshot and it assists with my explanation to the developers, but how does it actually work, under the hood and how many ways are there to create an AccName mismatch?

The AccName Computation

Fogetting the AccDesc part of this algorithm, we'll just look at the AccName part, as that is the only bit that can fail Label in Name, descriptions are supplementary and do no count.

Everything that is computed for the AccName has a precedence, and the one with the highest precedence (1) has the greater power and will ultimately be crowned the winner of the naming tournament.

Just to make my life easier, when I refer to "Contents" that is either the text content of the user interface component, the text content of any descendant node, or any valid naming method on any desecendant node

- If a user interface component or one of its descendants has only a

titleattribute (orplaceholderfor inputs, don't do this) as the name, then that is the AccName - If the node has Contents with a valid naming method and also a

title, then the AccName is the Contents and thetitlereverts to being the AccDesc - If the element can be named with a

<label>element, The - If the element has any of the previous naming methods, and an

aria-label, then the AccName will be the contents of thearia-label, irrespective of what the visible text is, the visible text no longer exists to the accessibility tree - If any or all of those previous naming methods are present and we add

aria-labelledbyon the element, with an ID reference to a valid text node, then not only does the text label no longer exist to the accessibility tree, but thearia-labelno longer exists, either. The AccName will become the computed value of thearia-labelledbyproperty, this attribute has the most power, it wins, always, it has a precedence of 1, it is the Undisputed Heavyweight Champion of ARIA naming and no contender can take that mantle from them.aria-labelhas a precedence of 2, it can only be defeated byaria-labelledby, but ifaria-labelledbyis not present andaria-labelis, thenaria-labelwill always win.

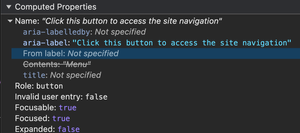

I have taken a screenshot of the computed name from the DevTools, for the example HTML I provided earlier:

In the screenshot above, the computed accessibility properties are presented in the Accessibility pane. There is an order and that order is the precedence or power of possible naming methods. As this is for a button, there are five possible naming methods to be considered, let's start from the bottom:

- title: Not specified, our element does not have a title, therefore, it cannot be considered for the AccName and will not be converted to the AccDesc

- Contents: "Menu", this text has a strikethrough, meaning its lost the naming battle

- From

label: Not specified, we do not have a label with a correct IDRef naming our button, so this cannot feature in the final computation aria-label: "Click this button to access the site navigation", ahh, this is what defeated the "Contents", becausearia-labelhas more power and will always winaria-labelledby: not specified, this heavyweight champion wasn't at this fight, so cannot be computed in the AccName

The result of the above is the aria-label is the AccName and the visible label is Menu. This is simply a case of don't use ARIA unless you really have to, the Contents provided a universally understood Accname and it was visible, too, so why use ARIA?

The computation, deeper

So, for aria-label and aria-labelledby to unleash their full power, they have to be present on the control itself. If a control contains descendants and one of those descendants has any of the two aforementioned ARIA naming conventions, then as far as the computation is concerned, they are the element's "contents". So, in an effort to try to simplify a pretty complex algorithm, the AccName is computed on a per element basis, all descendant nodes, irrespective of where they get their name from, are in fact the "Contents" of the target elements (the control in question).

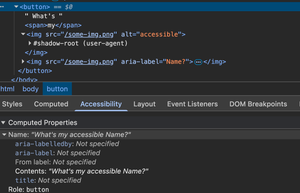

Let's consider this monstrosity of HTML:

<button>

What's

<span>my</span>

<img src="/some-img.png" alt="accessible">

<img src="/other-img" aria-label="name?">

</button>So, we have a button, with the following:

- Text Content of "What's"

- a

<span>element, with the Text Content "my" - An image with the alt of "accessible"

- Another image with an

aria-labelof "name?"

All of those four items will be computed as the Contents of the <button>, so the AccName becomes "What's my accessible name?". This is due to how the computation works, all of those are equal in the computation, as they are all Contents and the precedence does not apply to the final computed Contents, here, as each node only has one naming method to compute, and as they are all computed equally, they are concatenated according to the HTML source order (top to bottom).

It was worth mentioning the above, as the Accname algorithm does more than just compute the final name, it has other steps that compute the Contents string and it's at least interesting to have an idea how that part is computed, even if I am massively over-simplifying it. So, the takeaway is, that ARIA naming methods on descendant nodes are just computed as Contents, and Contents can still be neutered by both ARIA naming methods and the <label> element (if it is valid on that element).

The computation represented in the DevTools is captured, below:

Technically, the above would pass Label in Name, as the enitirety of the visible label "What's my" is present in the AccName, and according to WCAG, this is a "best practice", too.

The problem with this is it could create unnecessary pauses for screen reader users, or indeed, it could actually only read out the AccName in installments, requiring the user to use the virtual cursors to get at each descendant node. This did not happen with any of my devices, during testing (MacOS + Safari + VoiceOver, Android + Chrome + TalkBack, & iPadOS + VoiceOver and Safari), but these are all up to date. Users who have older devices that may no longer receive updates will get the older versions of screen readers and VoiceOver would probably have only announced the name in installments, especially on iOS and iPadOS devices. I can't confirm that, but those who remember role="text" to get VO to read a full string may suspect the same.

So, all contents are only ever computed as contents, irrespective of where the descendant nodes get their name from and anything that has a higher precedence will neuter all contents, a quick demo being:

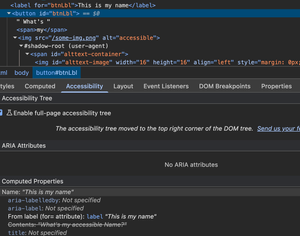

<label for="btnLbl">This is my name</label>

<button id="btnLbl">

What's

<span>my</span>

<img src="/some-img.png" alt="accessible">

<img src="/some-img.png" aria-label="Name?">

</button>So, what did I do there?

- I added an ID to the

<button> - I then added a

<label>where the value of theforattribute is an IDRef matching that<button> - I added the Text Content "this is my name" inside the

<label>

What we ended up with is the <label> neutered the Contents, as it has a higher precedence (3), so then the final computation is the AccName is computed from the <label> element. This would of course fail Label in Name, but I wanted to touch upon this, as contents features relatively low down the pecking order (4 for controls that accept labels) and because that programmatic relationship is made on the actual <button>, then it defeats the Contents and gets crowned the winner of the AccName fight. Only because the two ARIA naming methods were not present, of course.

The above image shows the browser has computed its the <button>'s AccName from the <label> element.

I've undoubtedly over-simplified the wizardry of the AccName computation, it's quite a complex beast, but having some idea of how it works can certainly help identify issues, especially those related to Label in Name.

Visually hidden text

This one is quite rare, but i have encountered it a few times and I genuinely do not know the intent behind it, but I flagged it, nonetheless, so let's consider the following HTML:

<button>

<span aria-hidden="true">Submit</span>

<span class="visually-hidden">Complete form</span>

</button>So, in the above example we have two nodes inside a <button>, the first for some unknown reason has aria-hidden="true" present, which obviously tells all the browser wizardry to ignore the contents of that node and its descendants (if any). So the wizardry will then look at the sibling node, which is not visible to anybody (unless they disable CSS) and will grab that to pass to the accessibility tree, then that becomes the AccName. Both of these nodes are Contents, but the first is ignored as a developer has told the browser to ignore it. We now have a mismatch, visually the label says Submit, but programmatically the word "Submit" does not feature in the AccName as it is "Complete form", so again, it fails. The first label does not need ARIA, the second one does not need to exist, "Submit" is universally understood to mean "Complete the form (or this part of it)".

I'm not a fan of AI, but I find it quite useful to create random images for things. In the above image, I wanted the shape the toddler is holding to be an outline shape of the word "Menu" and the shape-sorting cube's cutout to be an outline shape of the text "Click this button to access the site navigation", but I couldn't quite get AI it to do exactly as I wanted (garbage in, garbage out?). I also didn't want the child to look so upset, I wanted them to look frustrated. Still, it works well, as a light-hearted image highlighting the child's frustration at that shape not fitting anywhere in their cube. In some respects, the visible label needing to fit in the AccName is a bit like a poorly designed shape sorting cube the AI-generated youngster above is frustrated about.

Does the visible label fit in the AccName?

The sequence of visible characters must be present in the AccName, but just to make sure we understand that fully, let's consider some other examples:

| Visble label | AccName | Pas/Fail |

|---|---|---|

| Menu | Click this button to access the site navigation | Fail: The word "Menu" does not feature in the AccName |

| Our fab outdoor activities | About | Fail: The sequence of letters that forms the word about does not feature in the AccName, it sort of does, but it doesn't. the last two characters of "fab" and the first three of "outdoor" do indeed spell "about", however, the sequence is interupted by a space and that space was there to separate words, so we cannot create meaning from coincidences |

| Site Menu | Menu | Pass: The word "Menu" is present in the AccName, so this techically passes (it's not a best practice though) |

| Your Profile | Your User Profile | Fail: The entirety of the visible label is not present in the AccName as an uninterruped string. Having the word "User" between "Your" and "Profile" breaks that sequence |

| Profile Menu | Profile | Pass: The word "Menu" is featured in the AccName and the visible label features first (WCAG Best Practice) |

| Username | Username | Pass: This would be an actual "Best Practice", as say what you see would work perfectly here |

Does letter case matter? is "menu" the same as "Menu" or even "MENU"? I am by no means an expert, here, but, in my experience "menu" and "Menu" do not matter, because how would the software know I was pronouncing a word with a capital M at the beginning, verses one that doesn't and vice versa? This is something that WCAG also note in the Understanding Document, in that, the first letters of words capitalised does not matter. It does not clarify whether all caps matters, and I suspect that this could be due to an all caps word can sometimes affect the meaning in human language? I have never personally experienced an issue where the letters being all in uppercase in the AccName have caused an issue because the software has interpreted it as an initialism/acronym, etc. Voice input software isn't my usual input modality, I do use it for testing, but beyond that, I don't use it, so my experience is quite limited. I know that sometimes screen readers will output initialisms/acronys as opposed to the word, as they would parse it as the initialism/acronym, so whilst I cannot say for certain whether this is an issue or not, always err on the side of caution and follow WCAG's advice "When in doubt, where a meaningful visible label exists, match the string exactly for the accessible name".

So the key takeaway here is that the sequence of letters, as presented visually, MUST appear in that exact same order in the AccName. Whilst we do not typically pronounce punctuation, we do provide other audible cues to indicate it, such as short or longer pauses for commas, and spaces or full stops (periods), respectively. We do not ask a question like this: "do we, question mark" so these can be ignored, as can other punctuation symbols, such as colons, ellipses and what not, which is also mentioned in the Understanding Document. A space is a form of punctuation and whilst it does interupt a string, it does not necessarily change the meaning. It's quite common that company names are two or more words with no spaces, even product names often are and they may use kebab case (hyphenated words) or Pascal case (no spaces, each word starts with a capital, including the first word). Let's take the example of VoiceOver, a prime example of Pascal case for Apple's screen reader, let's consider this link:

<a href="https://support.apple.com/en-gb/guide/voiceover/welcome/mac" aria-label="VoiceOver">Voice Over</a>Using Voice Control (is this the only time Apple didn't use Pascal case?), should I command "Click, VoiceOver" (as I ordinarily would), it works as expected, as that space has not affected the meaning. People do not all speak at the same speed, so the software seemingly accounts for this, to an extent. Should I increase the pause between words, though, nothing happens. I am saying what I see, in that I am leaving a pause between two words, as that is exactly what I see. Let's see how the inverse works, with the following code

<a href="https://support.apple.com/en-gb/guide/voiceover/welcome/mac" aria-label="Voice Over">VoiceOver</a>Now if I say "Click, VoiceOver" a bit fast, nothing happens, should I slow it down a bit to account for the hidden pause, then it works. Does the sequence affect the meaning, given our very limited tests? I think the meaning remains the same, irrespective of the pause, however, it does affect operation, in that I ran into problems in both cases. Noted, I only used one voice input software, so my test is far from empirical, I also used the one that has a parent company that often requires their customers to do things a little differently (holding a phone and stuff), so perhaps I was destnied to find an issue? Okay, I agree, so let's use some others:

Voice Access on Android

Using the same limited tests as I did for Voice Control, I did not face the same problem. So the space did not affect the operation, in my tests.

Voice Access on Windows

I found this to be a little hit and miss, much of which related to my speech rate. When the visible label was just one word "VoiceOver" and Voice Access recognised it as one continuous word "voiceover", it would not activate the link, similarly, if my pause was too long in "Voice Over" it also did not activate the link.

Does spacing actually matter?

Going over the Understanding Document, it doesn't appear that spaces are mentioned, so I guess this is somewhat of a "grey area"? I guess the actual question isn't "does it matter for WCAG?", it's "what defines changing meaning in human language?" VoiceOver is known within the accessibility community and beyond as Apple's screen reader, voice over may mean Mike Myers giving Shrek a voice. If it causes an issue with some AT, as a pause is expected or it isn't, I'm of the opinion it has changed human expression sufficiently to affect the oucomes of my tests, but this is just one example, there are likely thousands, but here's some more:

- FedEx

- PayPal

- PlayStation

- WordPress

- QuickTime

- YouTube

- AppleTV (does this count?)

- MacBook (Apple do love Pascal case)

- ChromeBook

That's just what I found quickly, I know there are significantly more.

Given that I was able to find issues in two voice access platforms, and my testing was extremely limited, would I fail it? I would definitely mention it, I'd almost certainly fail it, but not without a deeper explanation:

- I would mention the first rule of ARIA, don't use it unless you have to, in the previous example, they absolutely do not need it

- I would list all voice access platforms I identified it as an issue in and explain where it does not work as expected

- I would mention that whilst WCAG does not explicitly state it fails, I am using my findings to flag an issue that is simple to fix and I, as the tester am interpreting a change in the expression of human language in that "VoiceOver" and "Voice Over" are not the same for all voice access platforms

- I would cover myself by saying it is seemingly a grey area, I'm happy to discuss it, but I only have my interpretation and what is written to go on and ultimately, it will be easier to correct a label than it would be to debate it

Fortunately, I have never encountered this exact issue before, I doubt it's common, this is just me finding nuance for further discussion. There is some related discussion on one of WCAG's issues, it doesn't get resolved, but it's interesting enough, and Alastair Campbell does state that "C O M P O S E" is not the same as "Compose" in human expression, so tentatively, I don't think Voice Over is the same as VoiceOver, as I would expect users to say what they see, and arguably, the space does matter here As I referenced earlier, WCAG say "When in doubt, where a meaningful visible label exists, match the string exactly for the accessible name" so that statement can in effect do a lot of heavy-lifting in a report.

Please don't go off my limited tests, though, I was somewhat conscious that I may have been leaving too long a pause between words or saying them too fast. I do not know if there are any settings in any of the voice access platforms that will allow users to account for their speaking rate. I couldn't find any on Voice Control, but maybe they are nested elsewhere.

We have already discussed the issues when the visible label isn't present in the AccName, even looking at how the sequence being broken with a space is likely a failure (sometimes?), but we also need to look a little beyond that, we need to consider how different tools operate.

I do not have all voice input software at my disposal, I do not have access to Dragon, which I know many users use as their main voice input software. I did use a few different ones in the previous section, though.

I want to speak specifically about Voice Control, the voice input software that comes built in with MacOS and iOS devices. It used to be the case that Voice Control expected the user to announce the full AccName, so commanding "Click, Submit" would not work for a bitton marked up like the one in the code example below:

<button type="submit" aria-label="Submit the form">Submit</button>WCAG state in their best practice that the visible label should be at the beginning of the string, yet, this did not used to work, as Voice Control was a bit of an outlier in that it expected the full string to be spoken. It has recently been "fixed", in that Voice Control now expects the visible label to be present at the beginning of the AccName, which aligns with WCAG's best practice. I believe most voice inputs software just expect the visible label to be present anywhere in the AccName string, so there is of course a difference.

Going back to my earlier recommendation, if we can just label a control with text and not use hidden text such as ARIA/visiually hidden text to modilfy or append the visible label in a non-visual manner, then that will always be the optimal strategy. There are occasions where this isn't always possible and we may need to append a control's AccName with additional text, but this is something we should do as a last resort.

In order to avoid creating this problem for users we can mostly simplify controls, in that if they have a text label, and that text label is adequate on its own to understand the control, then let that visible text be the AccName. We seldom need to neuter the AccName with ARIA, although there are of course times where information that is presented visually may require an AccName to be formed from more than one node, a date picker may be an example of where just "17" may not be sufficient as the AccName, if the cell has some other information clearly obvious information, perhaps, availability or whatever. None of this really matters for more traditional controls, such as a nav menu, profile menus, accordions and other elements that don't really need compound AccNames.

So, let users do what they will do intuitively, let them say what they see, and make it work for them the first time, don't leave users having to guess what something is called, as that doesn't sound like a fun game when they just want to get on with stuff, without having to faff around bringing up tools to help them operate a simple control.

Also, somethinng we didn't discuss, because I waffled (again), is give controls unique names. If there are two controls on a page, both of which have the same visible label and AccName "Settings", yet one is for the user's settings, the other is for site settings, what will happen when a voice input user instructs their software "click, Settings"? The software will likely bring up all matches, with a number overlay in essence "I found two, which one do you want?" and a user would then have to go through the additional step of saying "Click, 1", etc.